| Version 16 (modified by , 10 years ago) (diff) |

|---|

Table of Contents

The Layout Aspect: Describing And Manipulating Experiment Topologies in DETER

This page describes the model, specification and implementation of DETER's layout aspect. The layout specifies an experiment's physical or logical environment. It is a description of the elements that a researcher can manipulate and a characterization of how those elements communicate.

Different users of a layout view it different ways. A researcher studying the propagation of a security compromise may make use of a recursive tool to create a layout. Because the layout was generated by a recursive tool, a natural representation is in recursive chunks, which may result in a very compact specification.

The researcher has a different breakdown of the experiment than the generation tool. In their mind the layout may consist of a routing backbone, some enterprise networks, and a set of enterprise networks containing compromised computers. This breakdown of the layout can also be characterized in terms of chunks that are defined, not by the workings of the construction algorithm, but by the semantics of the researcher's experiment.

Finally, when the testbed realizes the layout, it will assign physical resources to each element and substrate. If the layout is heavily virtualized it may be helpful for the researcher (or testbed staff) to see the layout broken into chunks that map to physical machines in the testbed.

We call those different descriptions of the same layout views and the testbed supports creating a layout from one view, accepting additional views from users, and synthesizing new views internally. When viewing ore manipulating a layout, a user of the testbed can query the views available and select the one that suits their needs.

Inherent in a view is the definition of regions of semantic importance that can be shown, acted on, or extracted and reused by a researcher. These regions allow the testbed to present topological information to the user only when required, enabling users to deal with the cognitive overhead and information transfer costs of manipulating large topologies.

We describe a model that supports such multi-view topologies, an API that describes how to use the model and an initial implementation as an aspect in the Descartes interface.

Model

We describe the model in a bottom up fashion, first describing the atoms from which a view are constructed and then how to combine them into a full view. Once we have defined the view model, we discuss specifying and manipulating multiple views through the testbed interface.

The view model is not tied to the Descartes interface, and can be used by other tools for describing and manipulating topologies. The interfaces for creating a layout, requesting different views of it, and assigning new views are specific to Descartes.

The View Model

Each view is a description of a layout, and we begin by explaining how to describe such a layout, from simple, explicit descriptions, to more scalable and versatile versions.

The Fundamental Layout Model

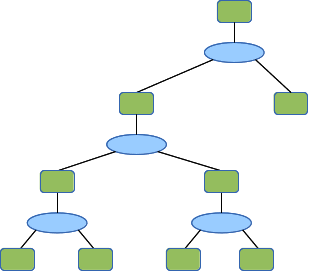

A DETER layout is a collection of experimental elements that can communicate with one another. The layout model consists of elements that represent those experimental entities and substrates which indicate the valid communications scopes. An element may be specialized depending on the capabilities supplied or required. A substrate includes limits on how the communication rate and delay when communicating through it.

The layout is represented as a bipartite graph where vertices are either substrates or elements. Edges are interfaces. Each interface connects an element to a substrate, indicating that the element can communicate on the substrate. An element may have additional communication constraints encoded in it as well.

Each element and each substrate has a unique name in the layout. Each interface also has a name, scoped by the element it connects to.

We stress that these are logical descriptions. Within DETERlab a substrate is usually realized as a virtual LAN (VLAN), but a substrate in general may capture a VLAN, a shared WDM frequency, a microwave line-of-sight or an open window across an alley. Similarly, an interface may represent a single card in a computer or a specific radio configuration. The mapping of interfaces or substrates to physical items is not always one-to-one. Similarly elements are logical communicating entities. They are specialized by the basic role they play in the experiment. Currently the most commonly encountered element is a computer, which may be a physical machine, a virtual machine instance, or even a process.

Element specialization is a fairly heavyweight extensbility mechanism. A simpler one is the ability to attach attributes to elements, substrates, interfaces, and the various sub components of specialized elements. Attributes are named strings where the names are scoped by the thing they are attached to. This allows tools that construct or manipulate topologies to annotate the topologies even if the core testbed does not use the information.

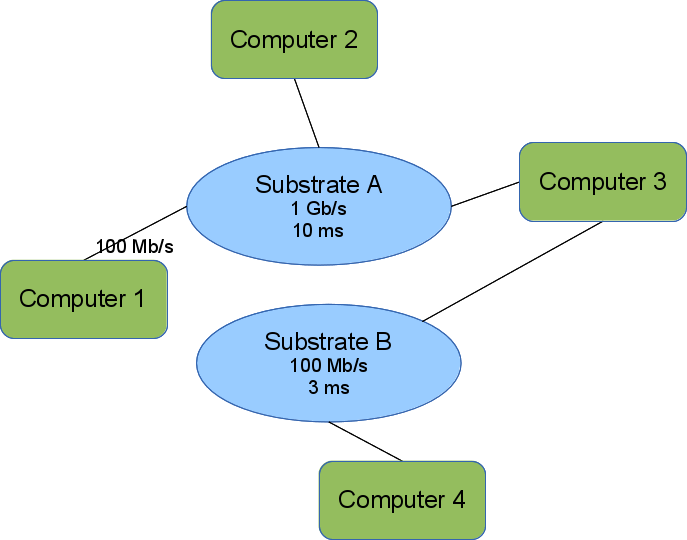

The image shows a simple layout encoded in our layout model. Computers 1,2, and 3 can communicate directly because they each have an interface on Substrate A. We omit the interface names. Computers 2 and 3 can send as fast as 1 Gb/s but experience a 10 ms delay before the first bit transmitted arrives at the receiver. Computer 1 is further constrained by its interface to a rate of 100 Mb/s, but sees the same delay.

Computers 3 & 4 can also communicate directly over Substrate B.

Computers 1 & 2 cannot communicate with Computer 4 unless Computer 3 forwards messages.

This also shows the bipartite nature of the graph. Substrates (blue ellipses) are only connected to computers/elements (green rounded rectangles). All interfaces connect an element to a substrate.

Scaling Using Regions and Fragments

The basic model specifies communication networks at a fairly high degree of abstraction while maintaining mechanisms for specialization. However, large topologies present several problems:

- Storing and transferring the entire layout can be wasteful if the researcher is only interested in manipulating or viewing parts of it

- There is no effective way to annotate subgraphs of the layout, though this is a natural way for researchers to specify and manipulate complex topologies

- There is no way to specify subgraphs of a layout beyond enumerating them

The region element addresses these shortcomings. A region is a placeholder in a layout that stands in for a subgraph, called a fragment. The region includes a natural language description of the missing subgraph and provides enough detail on how to generate the missing fragment. Note that fragments may also contain regions.

Fragments are specified outside the layout description. In fact, a fragment is exactly a layout description, so fragments can be combined easily.

A region specifies the fragment that it is standing in for by name. That name may be a pointer into a larger data structure that includes a fragment pool or a pointer to a service that can provide the fragment. Each region contains rules mapping the region's interfaces to elements in the fragment (of course the region's interfaces cannot be mapped to substrates in the fragment, because that would violate the bipartite rules of the graph).

In order to keep the names unique in the fully expanded layout, each region also contains rules used to rename the fragment elements and substrates when the region is expanded. There is some complexity to this that we expand on below.

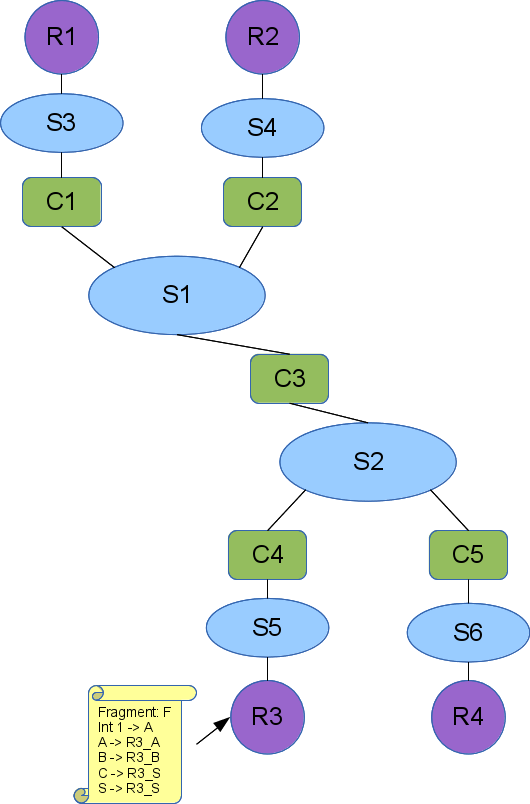

Here is a small layout with several regions defined:

This could be a wide are network with the leaf enterprise networks (or next tier wide area networks) replaced with regions (the magenta circles). We have shown the expansion rules attached to region R3. It will be replaced by a fragment named F, where R3's interface (int1) will connect to the element named A in fragment F. When the region is replaced, the elements A, B, and C in F will be replaced with R3_A, R3_B, and R3_C to maintain their uniqueness. We do not show the expansion rules for the other regions, but they follow this convention of prepending the region name.

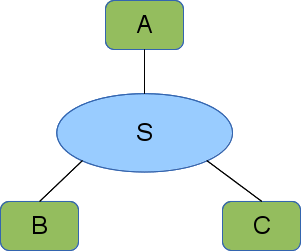

Fragment F looks like this:

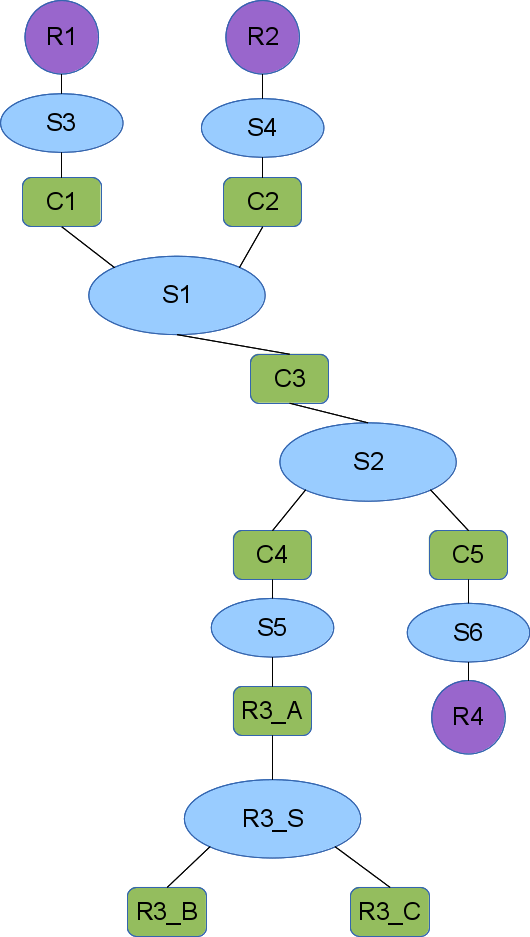

So that when R3 is expanded the overall layout looks like this:

Recursive Regions

Fragments can contain regions, so layout descriptions can be recursive. These layout descriptions are used to allocate testbed resources, so the model insures that all recursions terminate. Each region is assigned a non-negative integer valued level. The outermost specification of layout can has region levels assigned by the user. When a region is inserted into a layout as a member of a fragment that replaces a region, we assign all regions in that replacement a level one less than the region that was expanded.

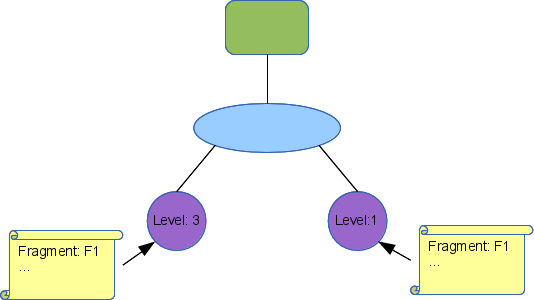

This is probably more intuitive with an example. Here is a layout:

And here is the fragment F1. The fragment and the top level layout are exactly the same, including the fragment recursively including itself in each of the regions in it.

When the testbed (or a tool) expands the layout the first time, this layout results. The labels are the level variable of each region.

Note that he two regions on the right side have level 0. We have left them in the diagram to show how recursions terminate. As we expend the regions again, below, we see that the level 0 regions are removed, as are the substrates that they were attached to. A substrate with one interface does not really constitute a communications context - there's no one to talk to. Removing the level 0 regions would be part of the first region expansion; level 0 regions never appear in real topologies.

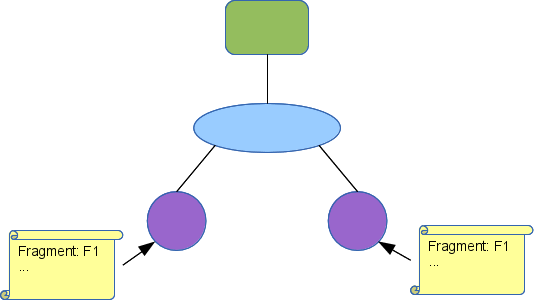

And those last remaining level 1 regions expand into single computers just as the first one did, leaving the full layout:

Naming and Recursion

We have been vague about how names are assigned to elements and substrates in recursions. In the simplest case, where the layout specifier does not care how those names are assigned, they can be assigned by the testbed (or tool). If the user wants a specific layout of names the pathname system can be used.

Each element or substrate in a layout was either named directly (at the top level) or results from an expansion of a region. By prepending the name of an element with the name of the region from which it was expanded, each substrate or element acquires a unique path name. That assumes that each expansion preserves the property than element and substrate names are unique, but the system can enforce this.

Should a user need control over each name, that user must supply an an explicit map of fragment name to layout name at each region element. The maps are bound to regions by pathname of the region.

The model supports hybrid solutions, where some areas of a layout include user-specified name maps and some regions of the layout are named by the testbed (or tool). The rule is that testbed-assigned names are provisional and can be overriden by specific user assignments.

Multiple Views

A researcher defines a layout by presenting the testbed with a view of it. The testbed may create other views and researchers may provide new views. Each view is named and has an associated description. Conventions will certainly appear for naming views with common functions. Researchers viewing or manipulating a layout can request the view that makes the most sense.

The most complex part of this is allowing researchers to provide a new view to the testbed. This is an essential feature, because researchers can provide the domain specific views that make working with topologies effective for them. However it is the most difficult case for the testbed,

If a researcher presents a view of an existing layout and both views have names assigned to all elements and substrates, it is straightforward to confirm that the new view matches the existing view(s) of the layout. Comparing a view with no names assigned to an existing view is an instance of the graph isomorphism problem. That problem is NP-hard (but not necessarily NP-complete), so confirming that the two views are isomorphic and adding the names to the new view can be computationally intensive. Middle grounds where some names have been assigned may be easier.

Implementations will support adding new views to the extent that it is possible to do so.

Interfaces

This section discusses the encoding of a view used for exchange and the interfaces to the Descartes interface that are relevant to manipulating layout views.

The exact format of these interfaces - the XSD defining the exchange format and RPC calls - are still in a bit of flux.

View Exchange Format (topdl v2)

When passing views from researchers to the testbed or from the testbed to a reseacrher Descartes uses an XML format based on topdl. This document defines version 2 of topdl that supports regions. There are a few other changes mentioned here.

A topdl topology element consists of 4 sections

- Substrates

- Elements

- Fragments

- Name maps

The substrates and elements sections are exactly as defined in topdl v1, except that regions are allowed as elements. A region includes a name and the fragment name that it expands to. The fragment name is either the name of a fragment in the fragments section, or a name that can be used to request the fragment from the testbed.

The fragments section contains fragment objects that are composed of elements and substrates. These may be referenced by region objects in the main topology or by region elements in fragments.

The name maps are a set of mappings, keyed by the pathname of a region. Each includes

- the region interface to fragment element mapping

- a fragment element or substrate name to global name mapping

- a description of the region

XSD for this format is available here.

Changes From Topdl v1

The primary changes from topdl v1 are:

- Region elements can appear in the element list of a topology

- Topologies contain a list of fragments that regions refer to for expansion

- Topologies contain a list of name maps that map the names of elements in a fragment to the names of the elements in the global topology.

The name maps are indexed by the path attribute that is updated when regions are expanded.

Other smaller changes include:

- The interface to substrate mapping is now 1-1. An interface connects 1 susbtrate to 1 element. Version 1 allowed an interface to map to multiple substrates, but that was unused and conceptually muddled.

- All elements have a name field. Element names must be unique in a topology. This is a simple, useful change. Most elements used in practice had and used names.

- The CPU element used to express the number of CPUs being described as an XML attribute rather than an element. It was the only entity in topdl that did that, and it no longer does. There is a count element in the CPUType definition now.

Layout Calls to the Experiment SPI

Researchers interested in working with experiment layouts manipulate the layout aspect of an experiment. It is possible to have multiple layouts definitions for an experiment that are divided into regions differently, as long as they all are isomorphic.

When a layout aspect is added, the testbed generates aspects of type layout and the following subtypes. This happens whether the layout aspect is added using experimentCreate() or addExperimentAspects() in the Experiments [wikiSPIDOcs#Services service].

- full_layout

- The layout with all regions expanded. The name is the layout aspect with "/full_layout" appended.

- minimal_layout

- The layout with no regions expanded and no fragments or namemaps attached. This is the quickest and dirtiest layout available for visualization. The name is the layout aspect with "/minimal_layout" appended.

- fragment

- A fragment of the given layout. The name is the aspect name with "/" and the name of the fragment appended. These are used to incrementally expand a minimal_layout

- namemap

- A namemap from the layout expansion. The name is the aspect name with the namemap pathname appended. These are used to incrementally expand a minimal_layout

A new version of the layout can be added at any time using addExperimentAspects(), but the call will fail for layouts that are not isomorphic to the experiment's current layout aspects. Adding a layout to an experiment without a layout aspect always succeeds.

Calls to addExperimentAspects or createExperimentspecify the type as layout, no sub-type, and a name for the view as name if needed. The data block is a topdl v2 description of the layout. As yet no incremental change format is defined, so changeExperimentAspect on a layout aspect always fails.

Attachments (9)

-

Simple_topo.png (51.5 KB) - added by 11 years ago.

Simple topology

- Fragment.png (11.9 KB) - added by 11 years ago.

- Unexpanded.png (68.4 KB) - added by 11 years ago.

- Expanded.png (71.5 KB) - added by 11 years ago.

- Recursion.png (18.5 KB) - added by 11 years ago.

- Recursion_Frag.png (17.6 KB) - added by 11 years ago.

- Recursion1.png (10.9 KB) - added by 11 years ago.

- Recursion2.png (14.2 KB) - added by 11 years ago.

- Recursion3.png (13.6 KB) - added by 11 years ago.

Download all attachments as: .zip