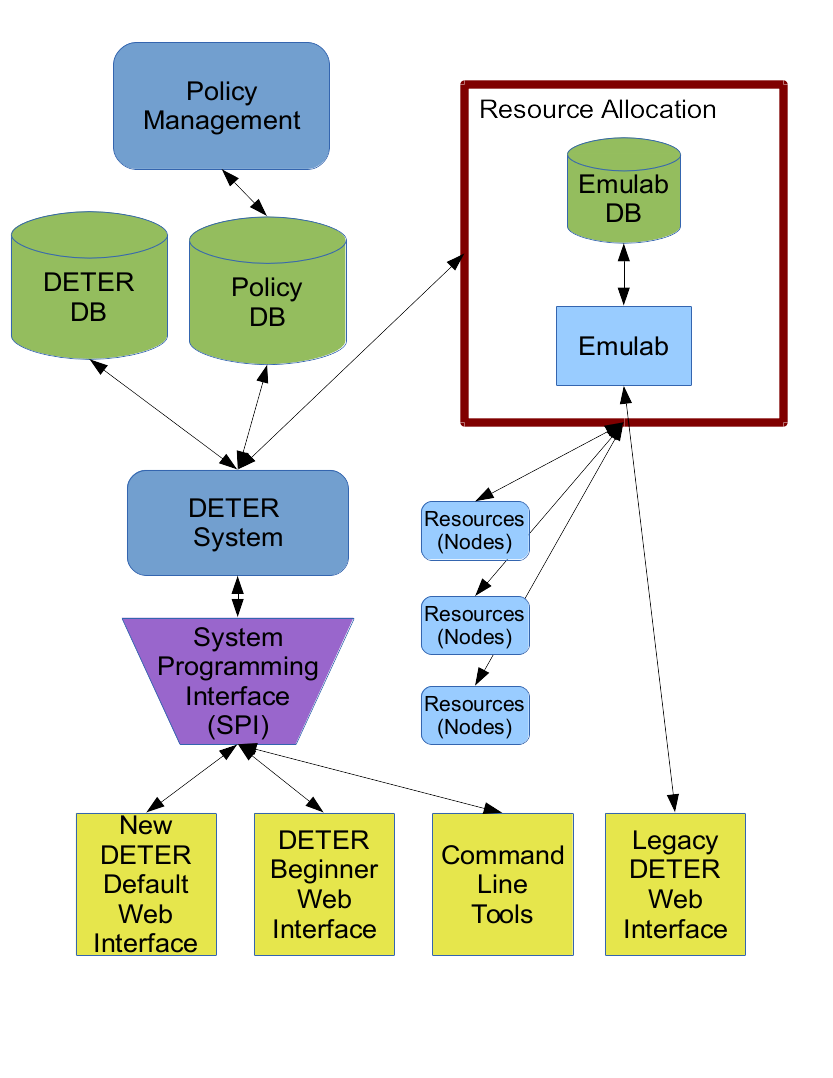

The DETER System Programming Interface (SPI) is a standard interface for manipulating fundamental DETER abstractions used to manage testbed resources and to marshall those resources into network and cybersecurity experiments. The SPI is analogous to an operating system's system call interface. It provides the fundamental abstractions that enable application programmers to make tools that are useful to researchers.

There are two motivations for building the SPI: first that the SPI is a context and programming framework for new DETER abstractions that subsumes the existing Emulab codebase cleanly. Second the SPI provides a context in which new developers can extend those abstractions to provide new functionality and to improve their scaling properties.

The SPI is fundamentally a tool-builder's interface. Researchers performing experiments or students performing class exercises are unlikely to access SPI methods directly, though we expect that higher level tools and interfaces will make the fundamental abstractions visible.

There are 6 first class abstractions that make up the DETER SPI. These are:

We describe each of these in more detail below.

This section motivates and explains two of the implementation design decisions that underlie the SPI: expanding the implementation beyond the Emulab abstractions and implementation, and using SOAP and web services to deliver the service.

The DETER research agenda drives the new abstractions, and it differs somewhat from the abstractions that drive the Emulab-derived code base. DETER is interested in sharing experiment infrastructure - including conducting experiments where multiple parties manipulate the environment based on different views of the world and different goals (multi-party experiments). Also, DETER is interested in multi-fidelity, large-scale experiments where the representation of the various partes of the experiment is guided by the researcher's design of the experiment. Finally, we think of experiments as having aspects that go well beyond the definition of the topology or layout, and the abstractions need to support this.

The Emulab code is based on simpler topology and experimentation models, and while its developers have been able to extend it to do more, our changes take the abstractions far enough that relegating the Emulab code to allocating local resources seems the cleanest way forward. Functions including user and project management will move into the SPI, though subsets of that function (basically current Emulab functionality) will remain available through the legacy interface.

As a last practical point Emulab-based codebase blurs the lines of some implementations between the webserver interface and the backend code. Building the SPI offers DETER a chance to solidify that interface and enable developer to build multiple applications on the DETER abstractions.

The SPI is built on the SOAP web services platform as a compromise between accessibility, extensibility, and support from tools. An important goal of the SPI is to allow multiple applications to use the DETER testbed. A web front-end for teaching cybersecurity classes that coexists with a web front end for experimenting on Internet anonymity are such a pair of applications. That may even look like two different testbeds from the outside.

To support that, the SPI must be platform independent. A web browser is a powerful application platform that the SPI must support. The SOAP/WSDL standards are a proven technology for such access. SOAP may be somewhat stodgier than a JSON/REST interface, but the differences can be constrained to encodings, and many tools for generating SOAP interfaces provide migration paths to other web services platforms.

Presently we take advantage of the fairly rich SOAP toolspace and have been able to use SOAP for access from a range of platforms from web browsers to multiple standalone programming languages.

The rest of this document goes into more detail on how to use the SPI.

This section describes the SPI abstractions and operations that application writers will use. We are concerned with how to put the concepts into use and how they interrelate with each other. Below we describe the detailed interface.

The SPI is broken up into services that implement the various abstractions. Each major abstraction presents its own service, and there are a few others for administration and information. Each service is a separate SOAP/WSDL service and has its own contact point. We break them up this way to keep the specification reasonably sized for both people and computers.

The services in the SPI are:

A profile is a collection of metadata attached to an abstraction instance, primarily to help users and administrators understand what the instance is bing used for. Users, projects, circles, experiments, and libraries all have profiles attached to them which describe those things. For example, a user profile includes the researcher's name and an e-mail address.

Profiles are self-describing, so that applications have guidance is what is being presented and how to display it. Each of the abstractions above has an operation called getProfileDescription in its associated service that returns an array of all the valid fields - called attributes - in that abstraction's profile. Each element of that array - each attribute - includes additional metadata that describes its purpose and presentation:

| Metadata | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Name | Descriptive name for the attribute, e.g. e-mail. All attributes have a name. |

| Value | The contents of the attribute. When retrieving a profile description, every attribute's value is empty |

| Description | Brief natural language description of the attribute, suitable for context sensitive help |

| Access | Whether a user can modify the data. Valid values are READ_ONLY, READ_WRITE, NO_ACCESS, and WRITE_ONLY

|

| Optional | True if the field can be omitted in a profile. All non-optional fields must be present when creating an instance. Applications may expect these fields to be present. |

| DataType | How to interpret the data. Valid values are STRING, Int, FLOAT, and OPAQUE.

|

| Format | A regular expression describing valid field entries. Applications can use this to check user input locally. Applications are not required to do so, but values for this attribute that do not match the expression will be rejected. |

| FormatDescription | A natural language description of valid input suitable for context sensitive help. The FormatDescription for a phone number field might be "10 digits, optionally separated by hyphens or parentheses." |

| LengthHint | A hint at how much space an application should to reserve for input, in characters. Applications can obviously ignore this. |

| OrderingHint | An integer that suggests to an application what order to display the field relative to others. Applications can ignore this |

Each instance has an associated operation, getUserProfile (projects have getProjectProfile, experiments have getExperimentProfile) that returns the profile for that instance as an array of attributes, as above. This profile includes the values for all the (readable) attributes.

Each instance supports a changeUserAttribute operation that allows the application to change the instance's attribute values. changeUserAttribute is used to change a user's phone number. Optional attributes can be deleted through this interface.

An application will use the profile operations in the following ways:

getProfileDescription, fill in non-optional fields (probably based on user input) and include that profile data with the creation request. All abstractions that have profiles attached require a valid profile as a parameter to the operation that creates them.

getUserProfile et al., and display all or some of the profile data.

changeUserAttribute, et al.

There is an administrative interface for changing the attributes in each abstraction's profile, but we expect the profile contents to remain relatively constant over time.

Currently the attributes that DETERLab includes in abstraction profiles are as follows:

For users:

| Attribute Name | Description | Optional | Access | DataType |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| name | Name | false | READ_WRITE | STRING |

| title | Title | true | READ_WRITE | STRING |

| false | READ_ONLY | STRING | ||

| affiliation | Affiliation | true | READ_WRITE | STRING |

| affiliation_abbrev | Affiliation (abbreviated) | true | READ_WRITE | STRING |

| URL | URL | true | READ_WRITE | STRING |

| address1 | Address | true | READ_WRITE | STRING |

| address2 | Address Line 2 | true | READ_WRITE | STRING |

| city | City | true | READ_WRITE | STRING |

| state | State | true | READ_WRITE | STRING |

| zip | Postal Code | true | READ_WRITE | STRING |

| country | Country | true | READ_WRITE | STRING |

| phone | Phone | false | READ_WRITE | STRING |

All users are required to have a name, e-mail address, and a phone number present in their profile, but may only change the name and phone number. (The e-mail address is used to validate the accounts.)

The e-mail and phone number attributes have formats attached:

| Name | Format | Format Description |

|---|---|---|

[^\s@]+@[^\s@]+ | A valid e-mail address | |

| phone | [0-9-\s\.\(\)\+]+ | Numbers, whitespace, parens, plus signs, and dots or dashes |

Because we expect applications to edit user profiles, there is layout information as well:

| Name | Ordering Hint | Length Hint |

|---|---|---|

| name | 100 | 0 |

| title | 200 | 0 |

| address1 | 500 | 0 |

| address2 | 600 | 0 |

| city | 700 | 0 |

| state | 800 | 0 |

| zip | 900 | 0 |

| country | 1000 | 0 |

| 1100 | 0 | |

| URL | 1200 | 0 |

| phone | 1300 | 15 |

| affiliation | 3000 | 0 |

| affiliation_abbrev | 4000 | 5 |

For Projects:

| Attribute Name | Description | Optional | Access | DataType |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| description | Description | false | READ_WRITE | STRING |

| funders | Funders | true | READ_WRITE | STRING |

| affiliation | Affiliation | true | READ_WRITE | STRING |

| URL | URL | true | READ_WRITE | STRING |

For Circles:

| Attribute Name | Description | Optional | Access | DataType |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| description | Description | false | READ_WRITE | STRING |

| true | READ_WRITE | STRING |

For Experiments:

| Attribute Name | Description | Optional | Access | DataType |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| description | Description | false | READ_WRITE | STRING |

For Libraries:

| Attribute Name | Description | Optional | Access | DataType |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| description | Description | false | READ_WRITE | STRING |

A user represents a researcher using the testbed. Most operations in the SPI are carried out on behalf of a user. Users must authenticate themselves to the testbed in order to carry out such operations. Users own other instances, for example a user owns experiments or projects that they create. Ownership is both an auditing construct - the testbed can determine which researcher configured which objects - and through policy assigns some rights to carry out operations. The owner of an experiment has rights outside those specified by the circles the owner belongs to.

Each user has a unique identifier, a textual userid. Permissions, resources, objects, etcetera are all bound to that userid. Authentication is the problem of binding a request to that identity.

In order for a user to carry out operations on the testbed, the user must log in to the testbed. When requests are made to the SPI they are made through a secure connection where client and server (that is user and testbed) are identified by an X.509 certificate issued by the testbed. The login process binds an X.509 certificate used to make a secure connection to a userid in the testbed used to determine rights. Users are authenticated through a password system.

The simplest way to log in through the SPI is to call the requestChallenge operation on the Users service. The caller specifies the sorts of challenges it can carry out and the server sends the input for such a challenge. Challenges can include hashing passwords and other mechanisms. Because the challenge and its response are passed through encrypted channels, we also support a clear challenge. In a clear challenge the caller submits a password in the clear. Each challenge is valid for a limited time - 2 minutes - and has a unique identifier so a response is bound to a specific challenge.

Once the caller gets a challenge, it calculates the response and replies to the challenge by calling challengeResponse on the Users service. If successful, the user is logged in and can begin carrying out operations.

The login process binds a user to an X.509 certificate, so the certificate and the challenge response need to work together. There are two ways to do this: if the user has no X.509 certificate from the testbed, the challengeResponse request can be made without a client certificate. In that case, the result of a successful challenge will include a signed certificate and a private key in PEM format that the user can use for future communications. The key is unencrypted, and it is the responsibility of the client to properly protect it.

If the user has an X.509 certificate - say from a previous successful challengeResponse exchange - the user can make the challenge response connection with that certificate, and the certificate/user binding will be complete and no new certificate created.

In either case, connections made with that X.509 client certificate will be treated as from the user until the user logs out using the logout operation on the Users service, logs in as another user as above, or the login times out in 24 hours.

Some web applications have trouble adding an X.509 certificate on the fly - especially those that run in browsers. To simplify the development of those applications, there is an operation in the ApiInfo service called getClientCertificate that returns a certificate issued by the testbed and an unencrypted private key, both in PEM format. This interface does not require a login and can be accessed through most web browsers, enabling a user to cut and paste the certificate into a local file for use with applications. The certificate is not logged in.

Additionally, a user can always get the server's certificate to check or add to a trusted servers file using getServerCertificate from the ApiInfo service.

Applications will have to carry out these challenges before doing anything else and can choose to log users out as well.

The Users service supports the operations described in the profiles description to allow applications to manipulate user profiles.

Many operations in the SPI require a user to agree with the operation before the operation becomes final. Users who wish to join a project or a circle request permission from the users who own or administer them. Administrators who wish to add users to their circles request confirmation from the users. Basically any operation that expands the rights of users requires the users in question to concur. In order to let users know when such changes are pending or desired, the SPI supports a system for managing short messages available through the Users service.

Notifications are these short messages. Notifications are sent by the system in response to actions requiring confirmation. This is not a general inter-user messaging system.

A notification consists of a the text of the message a unique identifier for the message, and a set of flags. The valid flags are:

| Flag Name | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Urgent | The message is more important than most messages |

| Read | The user has read this message |

Each user has a queue of notifications they can access. The getNotifications operation on the Users service returns an array of notifications for an application to display. Notifications can be filtered by source and by flags. The flags can be set using the markNotifications operation that specifies notifications by unique ID.

Applications will use these operations to:

Note that users generally cannot send notifications to other users. Only administrators and testbed actions do this.

The Users service provides operations for managing a user's password. A user who is logged in can change their password directly using the changePassword operation. The operation takes a user identifier and a password. Administrators can also use that interface to change other user's passwords.

If a user cannot log in - for example their password has expired or they have forgotten it - the application can use the requestPasswordReset interface to issue temporary credentials that can be used to set a user's password to a known value. When requestPasswordReset is called